நளி கடல் முகந்து செறிதக இருளி

நற்றிணை 289, மருங்கூர்ப் பட்டினத்துச் சேந்தன் குமரனார், முல்லைத் திணை

கனை பெயல் பொழிந்து

From time immemorial rains have always been played an important role in the evolution of human race. Just like the ancient civilizations in the Indian Sub Continent old Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations also found ways and means to harness water as they could with the available resources then. Mesopotamian civilization not only used Shadoof but also developed some of the earliest known canal system to harness water. Similarly ancient Egyptians used a system of basin irrigation to take advantage of the Nile floods and cultivate crops during the winter season. Kallanai dam over Cauvery built by Karikala Cholan around 150CE needs no introduction to the people of Indian Sub continent.

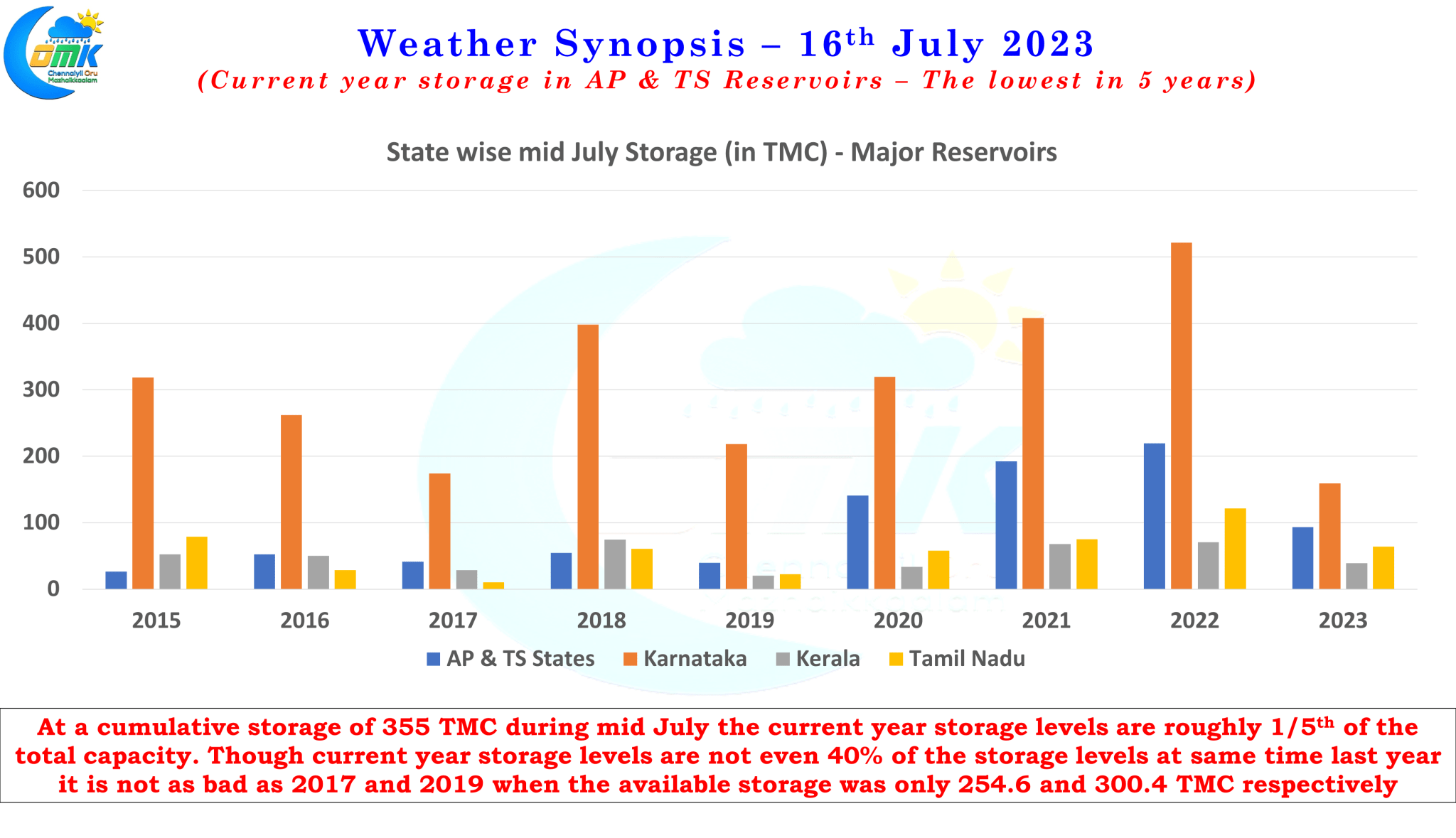

Since then as human population has evolved it’s dependence on monsoon and rains has only increased. Model day human civilization not only depends on rains for just agriculture but also hydro electric power through dams. The network of dams have allowed many places to get into agriculture which was traditionally not possible due to absence of regular water availability. It is in this context it becomes essential to track reservoir storage levels on a regular basis during the monsoon season. The dam managers have the unenviable task of being not only ready for potential floods when dams reach Full Capacity but also be aware of potential shortfalls during monsoon season to be ready for a drought scenario. With nearly 2000 TMC of potential water storage available in the reservoirs of South India dam levels remain a key indicator of monsoon performance for any given year.

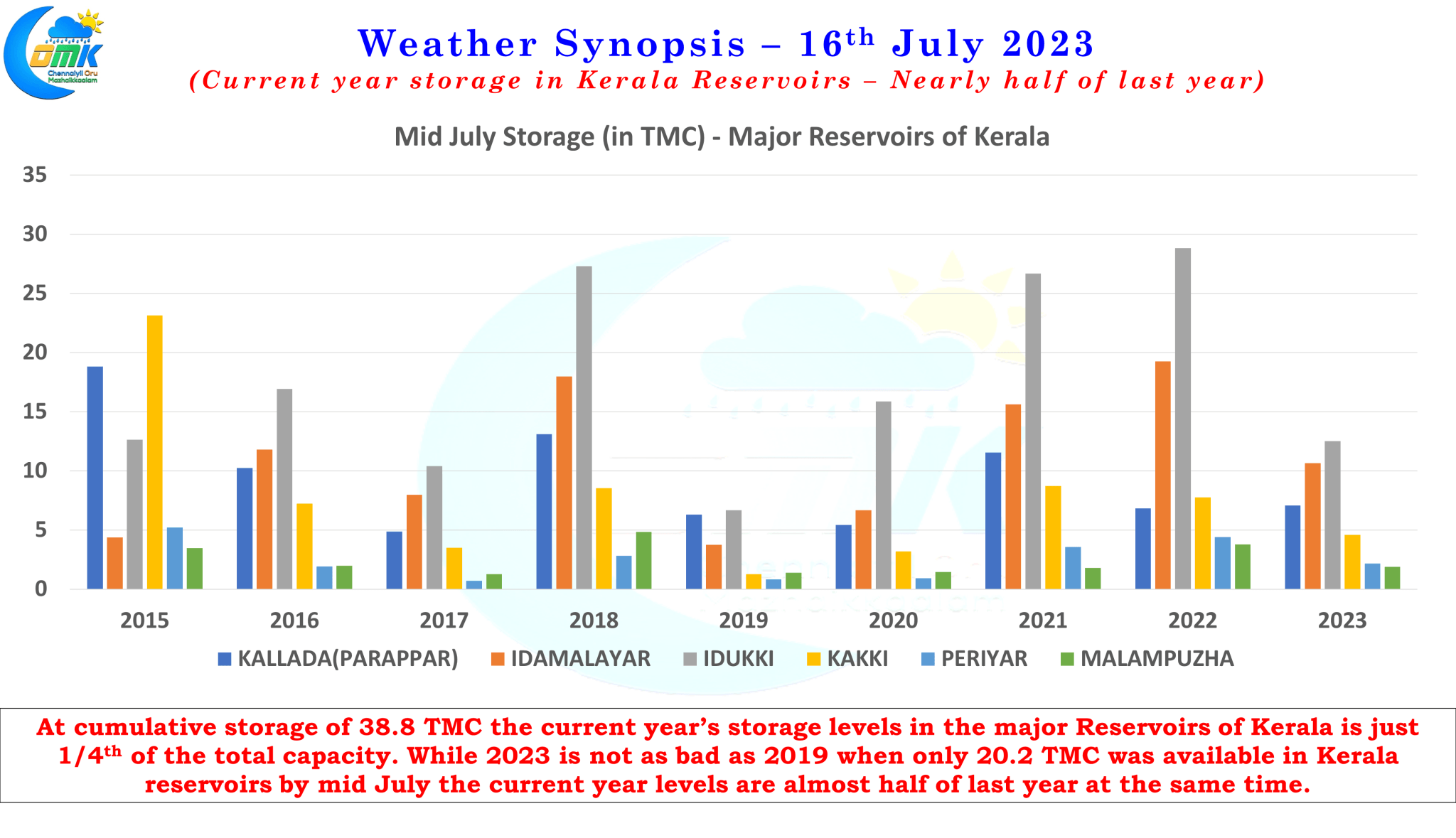

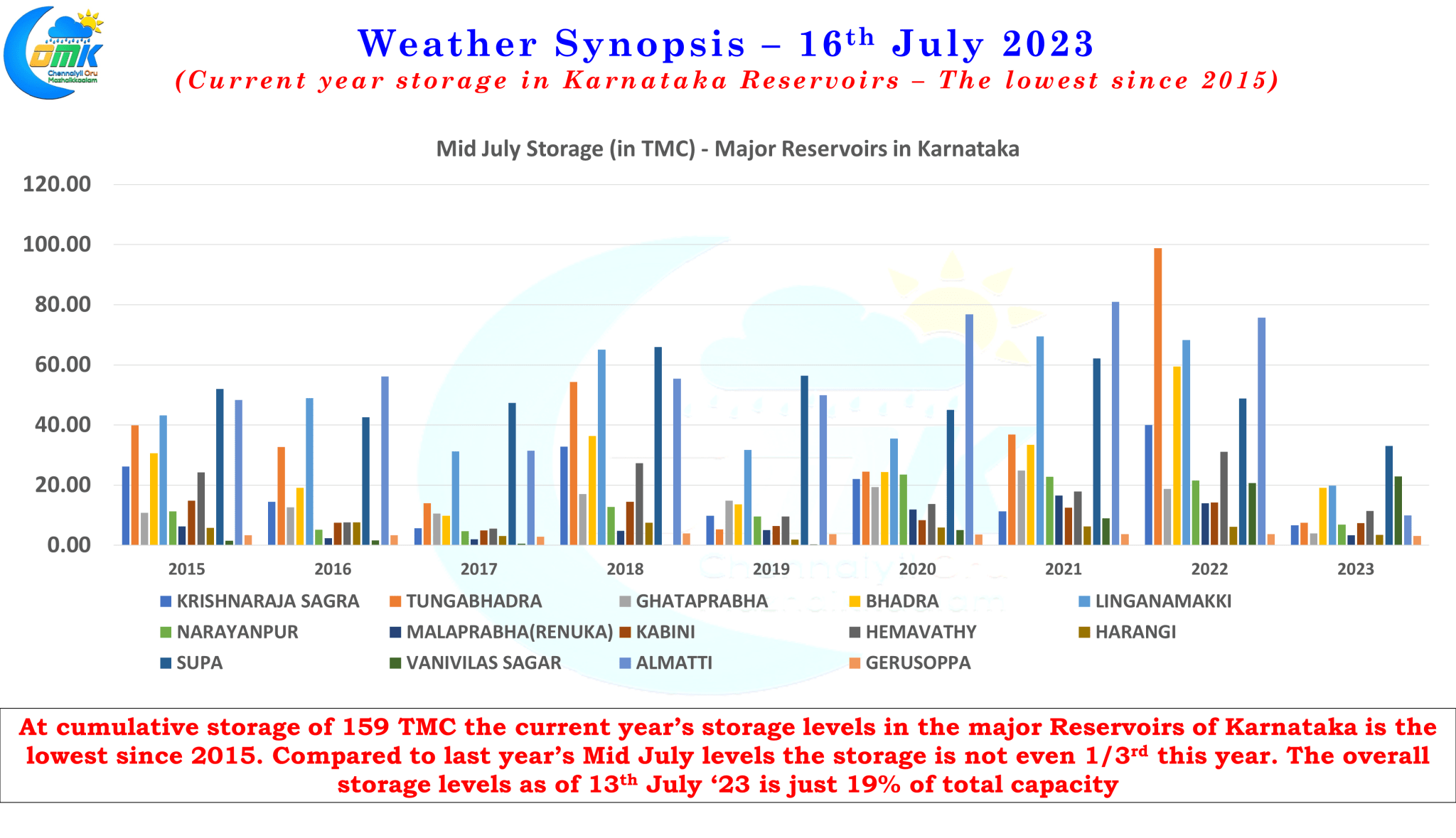

Over the past couple of years Southwest Monsoon has been fairly benevolent in terms of rains over Peninsular India particularly the catchment areas of Western Ghats. As a matter of fact by mid July 2022 the overall water storage in the reservoirs of South India had crossed the half way mark with just 45 days of monsoon season completed. We should not forget though for every 2022 there is always a possibility to have a year like 2017 when the available storage was not even 1/5th of the total capacity by mid July. Southwest Monsoon this year has been erratic with even surge days seeing limited influence over the Ghats. Nowhere the effect of the erratic monsoon is visible than the storage reservoirs of Karnataka. With just 19% storage available the current year is the lowest in terms of water availability since 2015. Interestingly 2022 was truly a bumper year with the dams almost 2/3rd full by mid July. If one compares the current year’s storage it is not even 1/3rd of last year at the same time.

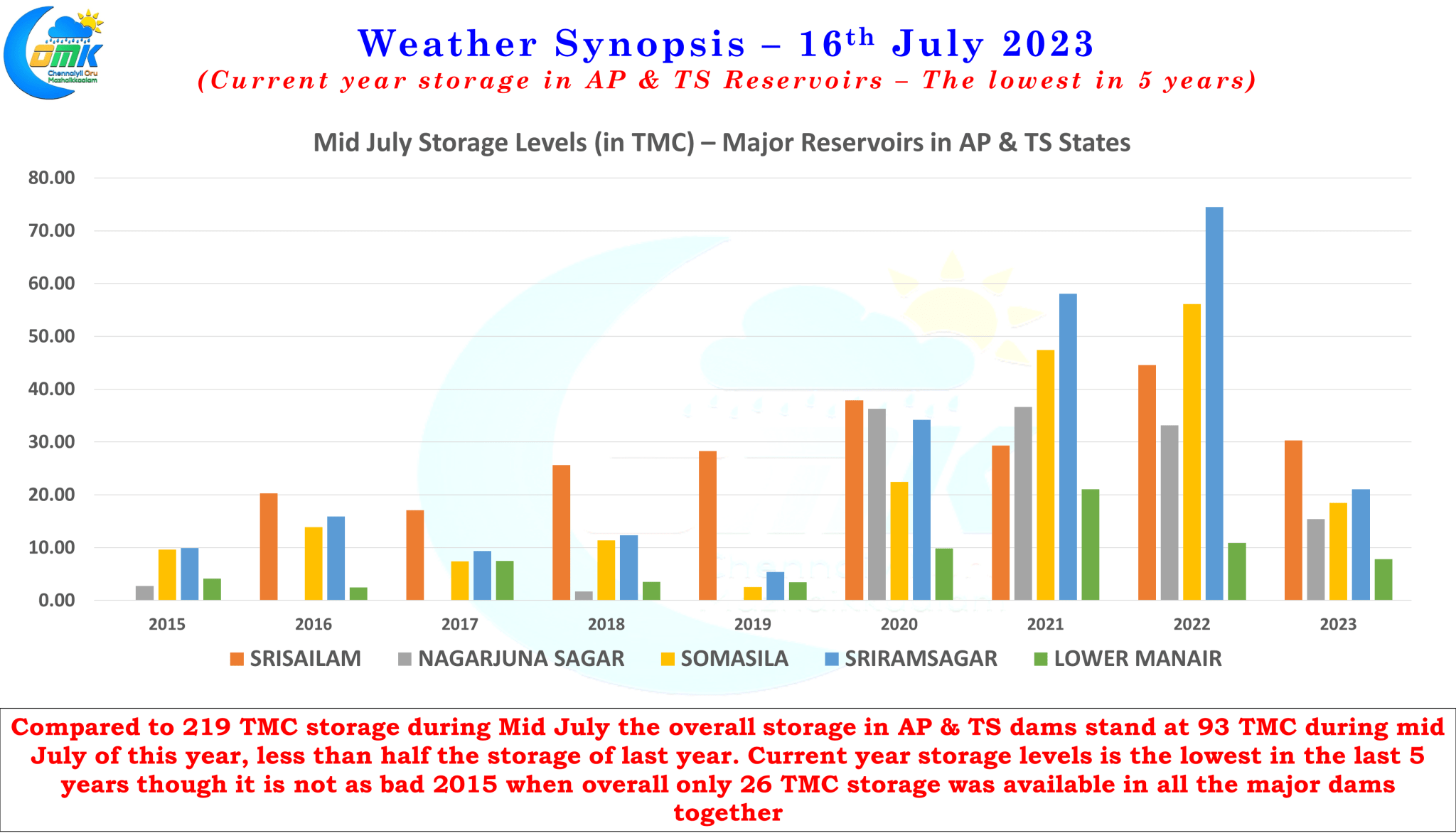

In a way the poor storage levels in Karnataka is also reflecting in the storage levels of the biggest reservoirs in South India, Sri Sailam and Nagarjuna Sagar. These two reservoirs are downstream to Karnataka and receive bulk of its inflows once the storage at the upper riparian reservoirs in the states of Karnataka and Maharashtra become comfortable. The overall Krishna Basin storage, which includes reservoirs like Thungabhadra, Almatti is currently at 1/5th of its total capacity resulting in poor inflows into downstream AP & TS states.

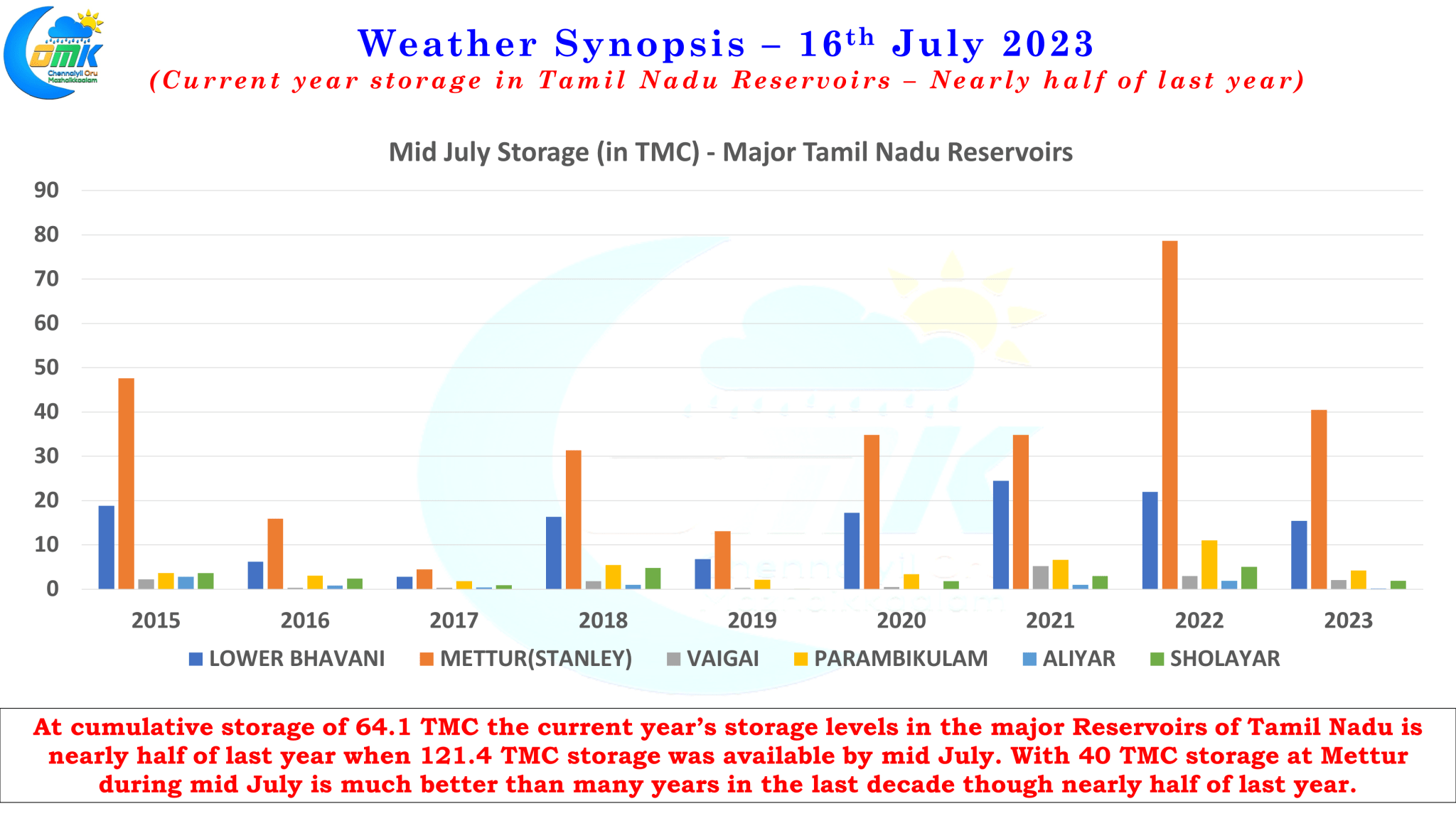

The story is similar in the Cauvery Basin as well though not as bad as Krishna Basin with overall storage at just 60% of the total capacity. At the time of writing the day’s post the inflows into Mettur Reservoir is just 176 cusecs indicating how critical things are getting in the Cauvery Basin. The Tamil Nadu government had opened the reservoirs for agricultural needs on June 12th this year hoping for another good monsoon year. As things stand situation in both Krishna and Cauvery Basins look grim with hopefully the upcoming spell of monsoon surge picking up things and preventing a potential flashpoint.